Socrates On A Screen? The Limits of .edu Reform

By Paul Glader on January 9, 2014

Domestic, Education Quality, MOOCs, Opinion, Required, Universities & Colleges

By Luke Trouwborst

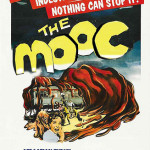

Everything changes, they say - but does education ever really change? Technology has wrought change across the American landscape, transforming even our interpersonal relationships. The recent rise of massive open on-line courses (MOOCs) seems to fit with the rest of these experiences: the internet makes stuff better. But throughout American history we see reformers trumpeting a “transformation” in education.

The Progressive movement of the early century tried to use emerging psychological theories to reshape the entire American curriculum - to no avail. In response, professor William Bagley argued that education would always resist change. While he’d prefer graduates of Johns Hopkins to Hippocrates when seeking medical help, he wrote that he’d always prefer Socrates to modern graduates of the Teacher’s College. Teaching, he claimed, was “ a fine art, not a technological art.”

While Bagley’s point still stands, the MOOC seems to mount a structural alternative to the status quo that is different than most attempts at revolution. Online courses offer, apparently, the same thing as the Ivy League courses: top-notch lecturers, identical readings, just a smaller (or non-existent) price tag. MOOCs are democratic. Campuses are elitist. Entrepreneurs like Sebastian Thrun at Udacity allow underprivileged children in Detroit to learn coding with WASPs at Stanford. Even storied campuses such as MIT and Harvard are moving (partially) online with the launch of “edX.” All this can be good, provided no one gets carried away.

The online education movement tempts gleeful iconoclasm. For years, the public has perceived colleges and universities as snotty institutions that over-charge for degrees with little practical value. MOOCs promise to refine the inefficiencies of academia in the pure fire of the free market. Bagley’s perspective is helpful to temper this enthusiasm. By 2050, technology may marginally improve the delivery of higher education, but don’t confuse the frosting for the cake. Here’s what we should expect - and what we shouldn’t.

New technology makes it easy to transmit facts, information, and data. Education in highly technical fields like computer science and math don’t require much more than that. This is why, in a recent interview, Sebastian Thrun announced that Udacity would be moving its focus almost entirely to technical fields. Long before MOOCs, we’ve heard of self-taught computer programmers. If you’re self-motivated, MOOCs are just another way to learn basic skills, but with degrees. Expect American universities to develop a diverse menu of choices for students, ranging from the traditional campus experience to entirely online courses you can take in slippers. Here, MOOCs recognize that some students see college as job training - and you don’t need four years in a dorm to learn many technical jobs or hard sciences.

“Education,” traditionally, is not just transmission of information or job training though. Education forms human beings. Robert Frost wrote that the purpose of college education was to instill students with “taste and judgement.” Simone Weil wrote that education was meant to give us the virtue of “attention.”

These subtle benefits of education don’t fit in formulas or spreadsheets. We acquire them in a three-way conversation between teachers, students, and the best that has been taught and said. Socrates didn’t shun a DVD lecture series for lack of BluRay players - he recognized that the teachers teach by asking students questions - and listening. And asking more questions. And, in Socrates’ words, caring about the “formation of their souls.” Skype with thousands of students will not do.

For instance, the hardest skill that many learn at college is the skill of learning. Not just anyone can learn from a lecture series and online chat rooms. Early data suggests this: most students taking advantage of online courses have already gotten degrees from traditional colleges, according to a UPenn report that argues MOOCs are “reinforcing the advantages of the ‘haves’ rather than educating the ‘have-nots.’”

We should be excited that MOOCs make information and job skills more accessible - just like libraries and Wikipedia. But lets not lose sight of this: eight times five MOOCs does not equal a university education.

Luke Trouwborst studies philosophy at The King’s College in New York City. This essay was originally an assignment for a persuasive writing course. Follow him at @luketrouwborst.

Related Posts

Internet highlights

- Online Casinos

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos In The UK

- Casinos Online España

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Online Casinos UK

- Best Online Casino Canada

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Best UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Betting Sites

- Uk Horse Racing Betting

- Top UK Casino Sites

- Casino Non Aams Sicuri

- Casino Non Aams Sicuri

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Crypto Casino

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Sites De Paris Sportifs Autorisés En Belgique

- Nhà Cái Uy Tín

- ブック メーカー 日本 おすすめ

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino En Ligne Argent Réel

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Siti Non Aams Legali In Italia

- Migliori Siti Casino Non Aams

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France 2026

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026

- казино онлайн україна

Tips & Pitches

Latest WA Features

-

Online Courses Are Expanding, Along With Questions About Who Owns The Material

-

Why Size Matters: Consolidation Sweeps Across US Higher Ed

-

Trend: Corporate U Employers Offering Just In Time Education To Workers

-

Subterfuge & Skullduggery In The College Rankings Game

-

“Instreamia” Shakes Loose Moss By Launching Spanish Language Mini-MOOC

Domestic, Education Quality, For-Profit, Friend, Fraud, or Fishy, K-12, Legislation, Opinion, Personalized Learning, Regulatory, Required, Universities & Colleges - Apr 29, 2014 - 0 Comments

Michael Horn: NCAA March Madness Followed By April Blunder In Online Learning

More In For-Profit

- The Economy Is Forcing Tuition To Fall Rapidly At Private, For-Profit Colleges

- Kamenetz: Jeb Bush As Controversial Leader Of Aspen Task Force on Learning & The Internet

- Columnist Ryan Craig: The Best Of Times Could Return As For-Profit Edu Invests

- Bubble Analysis: Trace Urdan on Why This Era of Ed Investing Could Be Different

- A Blended Path? How American Honors Cuts Cost of Four Year Degree by Over a Third

Community Colleges Cost of Education Domestic For-Profit Required Student Loans Universities & Colleges

Cost of Education, Domestic, Education Quality, Friend, Fraud, or Fishy, Opinion, Personalized Learning, Required, Technology, Universities & Colleges - Jan 17, 2014 - 0 Comments

Online Education As A Postmodern Societal Response

More In Technology

- MakerBot Academy: A 3-D Printer In Every Classroom

- Michael Horn: A Look Behind The Curtain At How A MOOC Is Made

- Koller, Khan and Agarwal At The NYT’s Schools of Tomorrow Conference

- Video: New NESTA Report, Three Steps To Assess Digital Innovation in Education

- Norwegian Teens Publish Their Own Guide To Teaching and Learning In Web 2.0

Blended Learning Education Quality International K-12 Open Source Education Personalized Learning Required Technology

Domestic, Education Quality, For-Profit, Friend, Fraud, or Fishy, K-12, Legislation, Opinion, Personalized Learning, Regulatory, Required, Universities & Colleges - Apr 29, 2014 - 0 Comments

Michael Horn: NCAA March Madness Followed By April Blunder In Online Learning

More In Friend, Fraud, or Fishy

- Online Education As A Postmodern Societal Response

- Apple Tightens Its 94% Choke-hold On The Education Tablet Market

- Michael Horn: Why Obama’s Proposals Won’t Entirely Revolutionize HigherEd

- Columnist Ryan Craig: The Curious Case Of HigherEd Accreditation

- McGraw-Hill Executive Speaking About Big Data: “Don’t look at us, look at Joe Camel”

Domestic Ebooks Education Quality Ereaders Ethics Friend, Fraud, or Fishy K-12 Publishers & Curriculum Required Textbooks

Reply